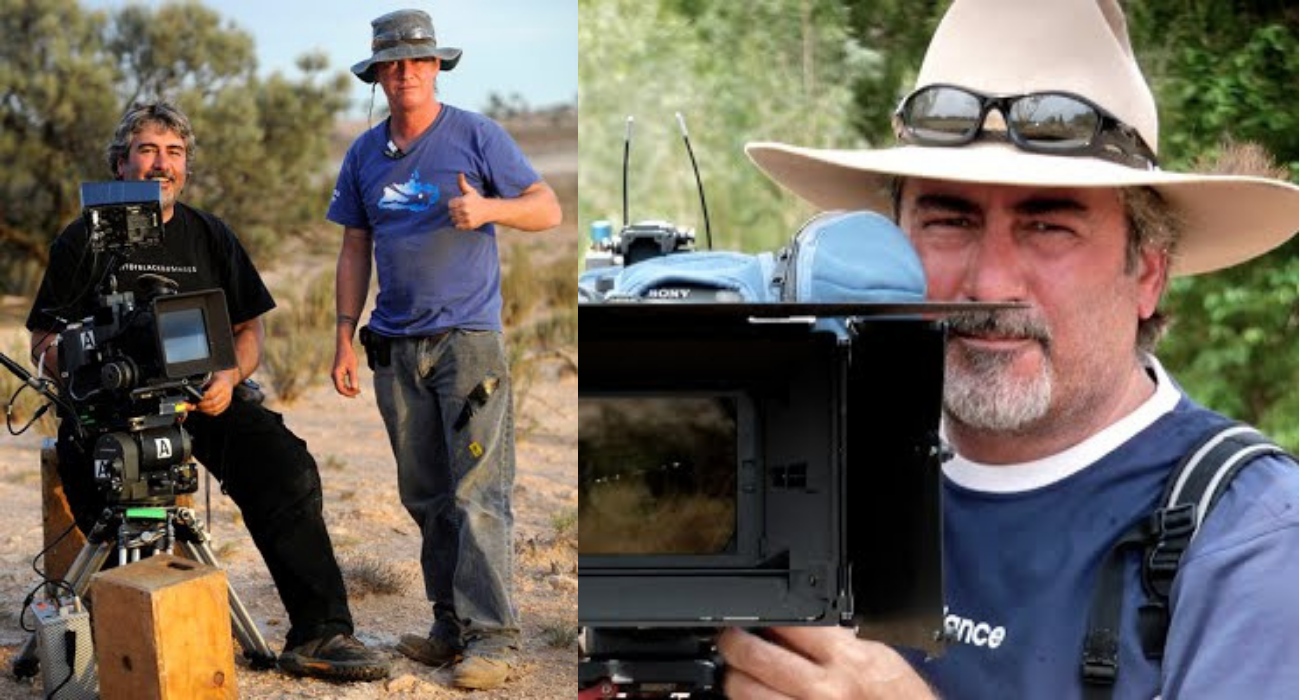

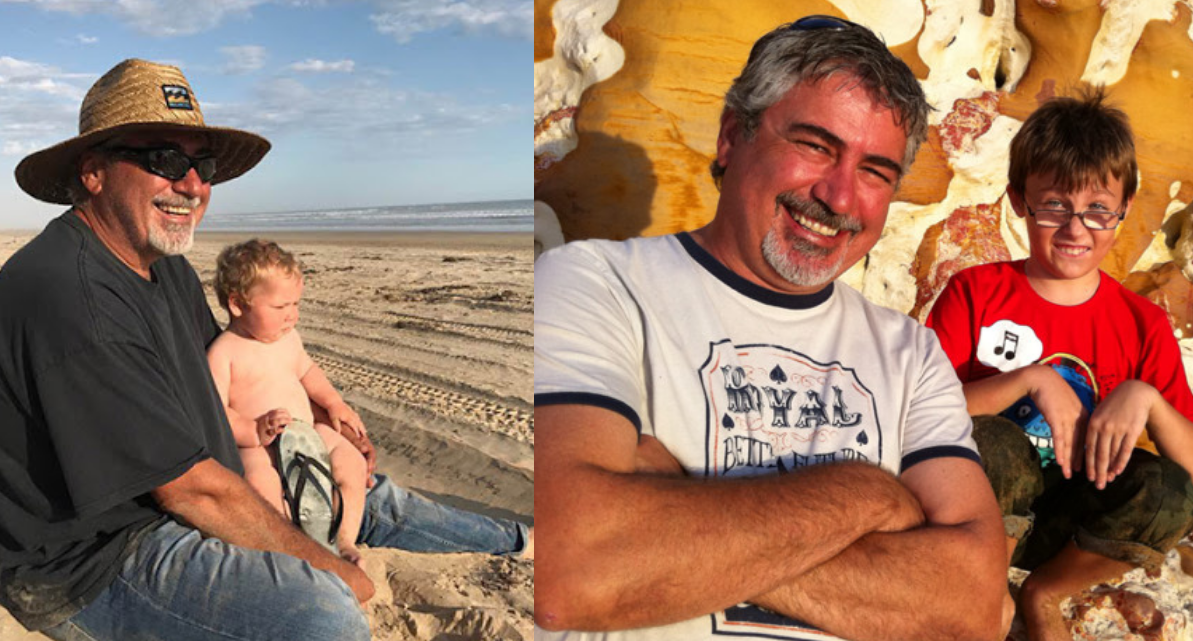

Allan Collins is a Cinematographer; an artist who describes himself as “always learning and always checking whether that was the right way to do it”. The questions of life constantly roam free in his mind: “how does the universe work?” and “why does the sun reflect off the moon?”. It’s these existential, visually vast thoughts that become part of his artistry. Ausfilm had the opportunity to chat with Allan about life as a First Nations Director of Photography hailing from Alice Springs, Northern Territory.

What indigenous nation do you come from?

On my mother’s side, that’s Wulli Wulli, from Queensland. On my father’s side, that’s Arrernte, from Alice Springs.

How did you get started in the screen industry?

I started at Imparja Television assisting with local regional commercials, and then I got to shoot the regional commercials. And then I moved to the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA), Australia’s largest Aboriginal media organisation, for a few years, who were producing longer form content. When I first started, I was a general production trainee so I did all kinds of things. I very quickly found that I naturally gravitated towards the camera. I really liked the whole process of taking images because I’d get to go to amazing places and get to meet incredible people and get to film.

CAAMA were doing half an hour episode series Nganampa Anwernekenhe, which is a language culture program. I probably did about 10 of them, maybe more. That series went for about 13 years. Over the years, that exposed me not only to filming in remote communities, Aboriginal communities, and even Torres Strait Islander communities, it also exposed me to the culture.

I look back at my past, and I think that helped create who I am, especially being around people that English was maybe a fourth or fifth language. Starting off at CAAMA Productions was an amazing base for a lot of us, like Warwick Thornton, Erica Glynn, Rachel Perkins, Jason Ramp, Peter Clarke and several others. We all came from that CAAMA mothership.

What made you want to work as a DOP?

It wasn’t something I knew at the beginning that that’s what I wanted to do, that’s for sure. I just really enjoyed making images and learning about technology and about light. This has been right from doing photography in high school. I also did one-year full time at AFTRS and I learned a lot but often I would be in the darkroom until the school shut at midnight just trying different things. Like what if I warm the water up by a couple of degrees, what happens to the film then? or what if I put more of this chemical in?

How have you noticed cinematography change and evolve over the years?

The technology has just changed so much. Like with Log formats, which are these low contrast formats that you film with, what we used to do was a low contrast transfer from our negative to the highest digital format of the time, and then we’d grade off there. Now, there are all these picture profiles in your digital cameras, whereas we’d actually have to do that to the negative.

Another example is a popular look of pulling the process, which would make it a very low contrast, a kind of soft look, as if set in a romantic past or something like that. Now, we’ll do this with a pull up. And I never really did a lot of pull processing, I just looked at it as an experiment. It wasn’t even a look that I liked but I did like to force the process, which is the opposite. I used to like underexposing the negative and over-processing it because that would give me a really high contrast and bit grainier, or a bit more textural look.

Even with the feature film Mad Bastards, it was forced processing. It’s not because I couldn’t expose, rather I was trying to use as much of the available light and light to such a low level with my lights, that the stuff in the background could still be just seen. But that’s like 500 ASA film stock. So, compared to now, we’ve got these cameras that quite happily will shoot a 12,000 ASA and they’re not all noisy.

But that’s what I loved about learning from actually mixing your own chemicals and processing your own film. You’re seeing what happened to it and you understand it in an organic, analogue way. With digital, you just change the number and it’s just faster for everyone. But I try as much as I can to remain analogue.

What kind of projects have you worked on? Did you have a favourite?

I have worked on many different types of projects over the years. I’ve done documentaries, music video, corporate videos, TV drama series and features. It’s difficult to choose a favourite because they all have some element that you’ll always love and you miss them all.

The documentary I worked on called Dhakiyarr vs The King, which won the Reuben Mamoulian Award, which is the Sydney Film Festival best overall film, and took me to Sundance Film Festival, was really special. I was the Cinematographer, and Co-Director with Tom Murray, who was also the Writer, and our collaboration on that was just great. People think that you can’t have two directors, but with two different people, you’re both being respectful to each other, and you make room for that other person to give their ideas. So, for us being together, we made a film better than either of us could have made, if it was up to one of us.

Sundance was just a massive culture shock. I come from the Alice Springs centre of Australia, and that was like being in an American Christmas movie or something.

Where’s your favourite region to film?

Places in Alice Springs are some of the most cinematic [part of the] country you can find anywhere. But it depends on your story and your budget, and whether you are co-funded by state film bodies. Every state’s got beautiful locations.

What’s your favourite camera?

It depends on what you’re trying to do. So, if it’s for a conventional sort of drama, then an ARRI ALEXA Mini. But really, any ARRI camera. Every camera and every format kind of has its benefits; whether they’re smaller and lighter for some things might be really beneficial like a DSLR or a A7S Mark III. You know, they’re really great little cameras, fantastic little cameras.

Who’s your DOP idol?

Ah, there’d be a few. I love Matthew Libatique. How he shoots was a very similar process, in the forced processing of that, of what I did when I did a short film called Road, which was shot on 35mm. I would look at how he’d do it, and then I read it in American Society of Cinematographers magazine. Every time he shoots something, you can’t really tell who shot it. I think he’s really good at being invisible. Like, every film just has its own unique special look and something that he’s doing is new. But the greatest will never not be Roger Deakins.

Who have been your biggest industry mentors?

Ron Johanson, the Australian Cinematographers Society President, because over the years, when I’ve been in different situations, he’s always come and helped me out.

What’s your favourite shot?

Oh, I love doing time lapses. It’s become really a passion. And every time you do a time lapse, it’s a challenge, because you don’t know what’s going to happen. I did time lapses that took five hours, and in that five hours, so many things can change. You can’t actually tell what you’re going to do at the beginning. Somehow, it’s using your intuition and your instincts and in all your experience, because you have to start moving your exposure or the various elements of time that you’re capturing, before they happen. Otherwise, it’ll be bumpy.

I just love time lapse because it’s almost impossible to predict exactly what’s going to happen, and so there’s this organic commitment to time, and it might not work.

What’s your favourite film?

I’d have to say Stand By Me is one of my all-time favourites. I also love Dead Man, the Jim Jarmusch, Johnny Depp film, and for totally different reasons. I love the cinematography of both of them and yet they’re completely different. Whenever I’m going to do something that I know is really important or really big, and I start looking for visual references, and I start talking to a Director about what they see their film looking like, and we’re trying to find a language to describe things, I’ll always find myself looking at both those films.

What’s your favourite First Nations films?

Beneath Clouds. That was the first feature that I ever shot.

What advice would you give to emerging DOPs?

Surround yourself with good people and people that share your passion so that you’re not just trying to learn overnight on how to work a camera.

But for me, being a part of the Australian Cinematographers Society was really important, because I got to see people that were far more experienced, and right up there in the industry. I could go to awards nights, and there is a little bit of a sense of “this is the people that really do this”, so that was kind of good exposure for me.

The ACS is getting even better. I’m part of a Diversity Committee and we’re trying to work out what the ACS can do in terms of diversity and inclusivity. Some of the people that are at the forefront of that were people that I knew a long time ago. They’re really stepping up and leading the way and I have my little say in there as well. That’s when I start thinking, gee, the ACS is good.

“So, to find people that are doing things that you want to do in a global sense, in a humanitarian sense, in what it is that makes you happy. Some people might be happy making commercials, and that might be exactly what they like doing. For me, as an Indigenous filmmaker, or cinematographer, I needed more than that. What was important for me too was: what are we doing for our community? What are we doing for our people? That’s why I was lucky to have that exposure that I did through CAAMA. Those connections to all those people go on.”

Allan Collins, Director of Photography

Featured Image Credit: Simpson Desert, south of Alice Springs.

Watch Allan Collins’ showreel: